Forward By Chuck Wilson

It was May 1, 1960, where the "May Day” holiday was celebrated in the Soviet Union. It was also at a time where Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were quite high.

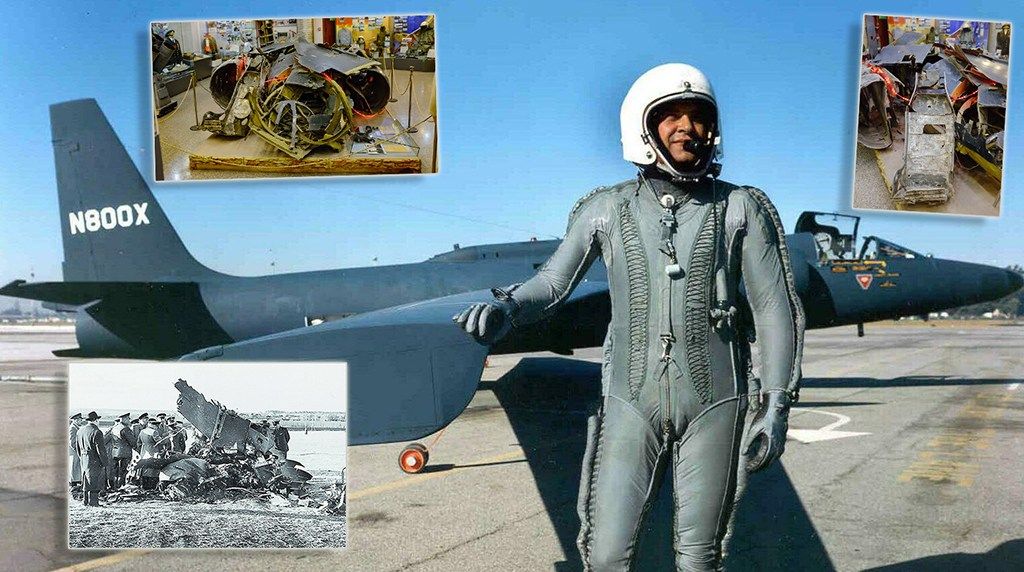

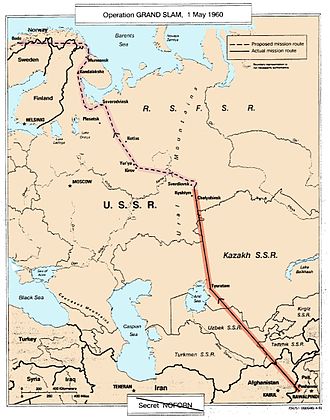

In the early hours of that day in May, at an airfield in Peshawar, Pakistan, a top-secret U-2 reconnaissance aircraft was being readied for an extremely sensitive mission sanctioned by the President of the United States. In the cockpit was Francis Gary Powers, the most experienced of the Central Intelligence Agency’s U-2 pilots, awaiting the specific order to launch. It came at 6:26 a.m. local time from the White House in Washington, D.C.

Previously the CIA’s U-2 penetrated Soviet airspace about 25 times. Over half of the "hard intelligence” the CIA had on the Soviet Union was from the U-2. But those missions only overflew a portion of the Soviet Union and returning to the base of origin. This May Day, the nine-hour, 3800-mile mission, would make a complete transit of the Soviet Union: from Peshawar Pakistan to Bodo, Norway. Unfortunately U-2 Pilot Francis Gary Powers, would not reach Bodo, Norway.

Powers was over halfway though

his mission, about 35 miles east of Sverdlovsk, when trouble struck. Eight Soviet surface-to-air SA-2 missiles were fired, five at the U-2 from three different

battalions with three more SA-2s fired, from a fourth battalion, mistakenly, at

a pair of MiG-19s: shooting down one of them. This is the description of what happened to that Top Secret U-2 flight, May 1, 1960.

Chris Pocock, the world-renowned U-2 British Historian, provides us with extract from his book, 50 Years of the U-2: The Complete Illustrated History of the Dragon Lady. This extract describes what happened that fateful day in May.

CHAPTER 10 MAY DAY

May 1, 1960

Powers climbed skywards from Peshawar in the usual

spectacular manner of a U-2. The roar of the J75 in the still morning air

startled Pakistani airmen all over the base. Powers made the single-click

signal to base on the UHF radio, to indicate that he was proceeding. Ericson

acknowledged with another click. From now on, there would be no radio contact

until he was ready to descend into Bodo over nine hours later. After 30 minutes

in the air, the U-2 approached the Soviet border in the same Pamir region as the

previous U-2 mission three weeks earlier. Looking ahead, Powers could see a

solid undercast stretching from the lee of the mountains on the Soviet side and

away into the distance. He cursed the late takeoff. All the celestial

computations would be out, and he would have to resort to dead reckoning as the

primary navigation aid.

Powers climbed skywards from Peshawar in the usual

spectacular manner of a U-2. The roar of the J75 in the still morning air

startled Pakistani airmen all over the base. Powers made the single-click

signal to base on the UHF radio, to indicate that he was proceeding. Ericson

acknowledged with another click. From now on, there would be no radio contact

until he was ready to descend into Bodo over nine hours later. After 30 minutes

in the air, the U-2 approached the Soviet border in the same Pamir region as the

previous U-2 mission three weeks earlier. Looking ahead, Powers could see a

solid undercast stretching from the lee of the mountains on the Soviet side and

away into the distance. He cursed the late takeoff. All the celestial

computations would be out, and he would have to resort to dead reckoning as the

primary navigation aid.

The PVO’s early warning radars soon detected the intruder, just as they had the previous overflight. The mission was easily plotted heading north, and the command post at PVO headquarters in Moscow was alerted. In the Soviet capital, the time there was one hour behind Pakistan. By 6am Moscow time, Biryuzov and all the top PVO generals had been woken and rushed to the command post, which was in the Defense Ministry on the bank of the Moscow River. Over at the Kremlin, preparations for the MayDay parade were well-advanced. It was due to start at 10 am. The entire political and military hierarchy were supposed to be there, including Biryuzov and his men.[1]

Defense Minister Marshall Malinovsky woke Premier Khrushchev and told him about the new intruder. The Soviet leader ordered that it be destroyed regardless of cost. All air traffic across the entire Soviet Union was grounded, so that radar operators could concentrate on the vital target. On the plotting screen in the PVO command post, Powers’ plane was moved steadily north. Interceptors were scrambled from Tashkent in pairs. As usual, they couldn’t climb high enough to get near.

Powers had been over denied territory for well over an hour

before he saw a break in the clouds. He spotted the Aral Sea off to the left in

the distance, and realized he was about 30 miles off course. While he was

making a correction, he noticed a contrail beneath him for the first time,

moving at supersonic speed in the opposite direction. More interceptors had

been launched from Tyuratam, which Powers was now approaching. But the pilots

here didn’t even have pressure suits, and they didn’t make contact. Powers

continued to monitor them through the driftsight, disappointed that the flight

had been detected so early, but relieved that the fighters remained so far

below. By now, he had levelled off at 70,000 feet.

Powers had been over denied territory for well over an hour

before he saw a break in the clouds. He spotted the Aral Sea off to the left in

the distance, and realized he was about 30 miles off course. While he was

making a correction, he noticed a contrail beneath him for the first time,

moving at supersonic speed in the opposite direction. More interceptors had

been launched from Tyuratam, which Powers was now approaching. But the pilots

here didn’t even have pressure suits, and they didn’t make contact. Powers

continued to monitor them through the driftsight, disappointed that the flight

had been detected so early, but relieved that the fighters remained so far

below. By now, he had levelled off at 70,000 feet.

There were thunderclouds over the launch site. Powers switched on the B-camera as planned, but noted that the intelligence would be less than 100%. There were three S-75 batteries at the missile site, but one was unmanned because of the Mayday holiday, and the U-2 did not fly within the engagement zone of the other two. Now the solid undercast resumed. Powers tried a sextant shot, as a cross-check on the compass. It seemed to be accurate.

Pressure in Moscow

The PVO commanders in Moscow now expected the U-2 to turn northeast or northwest, to cover the same objectives as the three previous intrusions. But it headed straight on north. Biryuzov was fielding angry phone calls from Malinovsky, and even from the Kremlin. "It’s a scandal,” Khrushchev berated him. "The country gave all the necessary resources to the Troops of the Air Defense, yet you cannot destroy a subsonic plane!”[2]

It wasn’t that easy, though. The PVO was still learning how to operate the new missiles, and how to properly co-ordinate all the radars involved. It took nearly a day to dismantle, move and set up an S-75 battery. Once established, it took up to five hours to bring the battery to combat readiness. Even then, the diesel generators couldn’t be kept running indefinitely. If there was no other source of power, they had to be turned on. That caused another 13-minute delay. If the target aircraft was flying at high subsonic speed, it had to be detected 80 miles away, in order to slew the missiles, acquire the target with the engagement radar, and fire. But the surveillance radar which began the search and acquisition sequence, had a range of only 110 miles against a fighter-size target. There wasn’t much scope for error or delay. Furthermore, each battery could only remain at the highest readiness state for 25 minutes.[3]

By 0800 local time the U-2 had passed Magnitogorsk, and was clearly heading for the central Urals. Here were many nuclear weapons-related facilities which the USSR had taken great trouble to isolate from prying eyes in so-called ‘secret cities’. Unlike further south, the skies over the Urals were fine and clear - great weather for aerial reconnaissance!

Autopilot Problem

Powers saw the clouds thinning below him. He peered through the driftsight, trying without success to relate the emerging ground features to his maps. Fortunately, his flight plan showed a radio beacon in this area, so he tuned the ADF. The specified frequency was correct, though the callsign was wrong. The radio fix helped him re-establish the correct course. He was some way south of Chelyabinsk. But with one problem solved, another one emerged. The autopilot mach sensor malfunctioned, causing the nose to pitch-up. Powers retrimmed, flew manually for a while, then re-engaged the autopilot. The plane flew fine for a while, then pitched up again. Powers repeated the corrective action, with no better result. Faced with the prospect of flying manually for another six hours, he nearly turned back. After all, the U-2C Flight Handbook clearly stated that "proper autopilot operation is mandatory...to satisfactorily accomplish the mission.”[4]

"An hour earlier, the decision to turn back would have been automatic,” Powers later recalled. "But I was more than 1,300 miles inside Russia, and the visibility ahead looked excellent. I decided to go on and accomplish what I had set out to do.”[5]

An SA-2 regiment was located at Chelyabinsk. It was brought

to highest alert status. A surveillance radar acquired the U-2, but the

‘hand-off’ (transfer) of target from radar to missile battery went wrong. One

of the radar circuits at the battery fused, and the missile control officer

searched his screen in vain.[6]

An SA-2 regiment was located at Chelyabinsk. It was brought

to highest alert status. A surveillance radar acquired the U-2, but the

‘hand-off’ (transfer) of target from radar to missile battery went wrong. One

of the radar circuits at the battery fused, and the missile control officer

searched his screen in vain.[6]

A Sukhoi-9 interceptor was thrown into the hunt. The pilot

took off and flew south towards the approaching target. But he had been

scrambled too early: running short of fuel, he was obliged to descend and land

at on the small airfield at Troitsk. This didn’t even have a runway; it was the

first time anyone had landed a Su-9 on grass!

A Sukhoi-9 interceptor was thrown into the hunt. The pilot

took off and flew south towards the approaching target. But he had been

scrambled too early: running short of fuel, he was obliged to descend and land

at on the small airfield at Troitsk. This didn’t even have a runway; it was the

first time anyone had landed a Su-9 on grass!

Powers flew on, crossing unscathed over Chelyabinsk. He was relieved to see no interceptors beneath him. The next target was the USSR’s first plutonium production complex which was located amongst the lakes and forests to the east of Kyshtym. Powers was now flying over the scene of a serious nuclear accident three years earlier which the USSR had managed to hide from the world. High-level nuclear waste which was kept in solution within an underwater concrete tank had exploded and released 70-80 metric tons of radioactive debris into the atmosphere. Over 200 towns and villages with a combined population of 270,000 had to be evacuated. Despite the massive scale of this disaster, only the vaguest reports had yet reached Western intelligence (and it would be another 29 years before the full story emerged from behind the Iron Curtain).[7]

More Interceptors Launch

Powers turned onto a northeasterly heading which would take him towards Sverdlovsk.

The PVO had now repositioned two MiG-19s belonging to the

356th Regiment from Perm to Koltsovo airbase, on the military side of

Sverdlovsk airport. They were being hurriedly refueled. The same regiment had

participated in the chase for Mission 4155 three weeks earlier. Another two

Sukhoi Su-9s were also on the ramp. They were on a delivery flight from the

factory in Novosibirsk to Belorussia, and had only stopped at Koltsovo to

refuel. But the Su-9s had been held up there over the MayDay holiday, by the

same poor weather which had caused Mission 4154 to be postponed three days

running.

The PVO had now repositioned two MiG-19s belonging to the

356th Regiment from Perm to Koltsovo airbase, on the military side of

Sverdlovsk airport. They were being hurriedly refueled. The same regiment had

participated in the chase for Mission 4155 three weeks earlier. Another two

Sukhoi Su-9s were also on the ramp. They were on a delivery flight from the

factory in Novosibirsk to Belorussia, and had only stopped at Koltsovo to

refuel. But the Su-9s had been held up there over the MayDay holiday, by the

same poor weather which had caused Mission 4154 to be postponed three days

running.

The pilot of the second Su-9, Captain Igor Mentyukov, had no pressure suit and the plane was unarmed. But Gen Yuri Vovk, who commanded the fighter-interceptors in the Sverdlovsk district, knew that the Su-9 had a better chance of reaching the high-flying target than the MiGs. He ordered Mentyukov to takeoff. As the Su-9 climbed away, Vovk radioed to Mentyukov: "There is a real target at high altitude. The mission is to destroy the target, to ram it...Dragon has ordered this.” Dragon was the personal codename of Marshall Yevgeny Savitsky, the commander of all PVO fighter units, Vovk reminded Mentyukov.

Without a pressure suit to protect him if the cockpit depressurized, Mentyukov was facing almost certain death if he were to fulfill the mission. Under the usual tight control from the ground, Mentyukov was directed to turn towards the target. He jettisoned his drop tanks and accelerated to Mach 1.9. As he climbed through 65,000 feet, the ground controllers told him that the target was only 25 kilometers away. They could see both the interceptor and the intruder on their radar screens. But in the black sky all around him, the pilot could see nothing. Mentyukov switched on his radar, but the screen showed only interference. This was strange - it had worked just fine when he tested it just after takeoff.[8]

The supersonic Su-9 was closing fast on the subsonic U-2, and the controller ordered him to switch off the afterburner. Mentyukov protested that this would cost him altitude, but the controller repeated the instruction. The pilot complied, and the Su-9 began descending as it passed the still-unseen U-2. The ground controller now told Mentyukov he had overshot. After some mutual recrimination between pilot and controller, Mentyukov reported that he was running short on fuel. The controller told him to return and land, and the two MiG-19s were scrambled instead.[9]

The Missiles Engage

Meanwhile, Powers had reached a point some 35 miles southeast of Sverdlovsk. At the PVO district headquarters, the command post which controlled the missile batteries was on a separate floor to Gen Vovk’s command post which directed the fighter interceptors. And the overall district commander was away on a training course. It was a recipe for confusion.

The missile command post identified the nearest missile

battery to the approaching plane, and passed its range, altitude and bearing to

the site, with orders to fire. The commander of this battery was also away, and

the task fell to his deputy, Major Mikhail Voronov. His three radar operators

had to acquire the target by means of the two narrow fan-shaped beams generated

by the Fan Song. It was a difficult task, since the U-2 was passing

close to the edge of the battery’s engagement area. Eventually, the operators

managed to switch the radar into automatic tracking and missile guidance mode,

and a firing solution was obtained. Voronov checked his own screen and ordered

the launch, a salvo-fire of three missiles. The launch control officer

hesitated, and Voronov yelled at him to fire. The solid fuel booster at the

rear of one V-75 missile ignited, and it roared away. Another two missiles

should have followed seconds later, but they didn’t; the target was fast

receding and the fire control system calculated that it had now passed beyond

range.[10]

The missile command post identified the nearest missile

battery to the approaching plane, and passed its range, altitude and bearing to

the site, with orders to fire. The commander of this battery was also away, and

the task fell to his deputy, Major Mikhail Voronov. His three radar operators

had to acquire the target by means of the two narrow fan-shaped beams generated

by the Fan Song. It was a difficult task, since the U-2 was passing

close to the edge of the battery’s engagement area. Eventually, the operators

managed to switch the radar into automatic tracking and missile guidance mode,

and a firing solution was obtained. Voronov checked his own screen and ordered

the launch, a salvo-fire of three missiles. The launch control officer

hesitated, and Voronov yelled at him to fire. The solid fuel booster at the

rear of one V-75 missile ignited, and it roared away. Another two missiles

should have followed seconds later, but they didn’t; the target was fast

receding and the fire control system calculated that it had now passed beyond

range.[10]

But the first missile was streaking towards the U-2, some 14 miles distant. The command guidance link from Voronov’s battery to the missile was properly established, and the missile accelerated past Mach 2. It would take only a minute to reach the target, even though the U-2 was at 70,000 feet. The fire control computer issued the appropriate changes of course as the missile closed on the target from behind. After flying for some 12.5 miles, the second-stage would be exhausted, and the missile would then continue on a ballistic trajectory.

Powers had no idea he was under attack. As the missile neared, he made a 90-degree left turn as shown on his flightplan, in order to line up on the next intelligence objectives on the southwestern fringes of Sverdlovsk. He was making routine notes of the time, altitude, speed and EGT when "there was a dull thump, the aircraft jerked forward, and a tremendous orange flash lit the cockpit and sky,” he recalled. It was 0853 local time, and his long ambitious flight had been cut short after only three and a half hours.[11]

Shoot-Down

The missile had exploded some way behind (and probably below) the U-2. The V-75 missile’s warhead was designed to explode upon command guidance, or automatically when it reached close proximity to the target. A direct hit was not required, because the 180-kilogram fragmentation warhead broke up into 3,600 shotgun-type pellets, which were projected forward in an expanding cone.[12]

The pellets hit the tail and rear fuselage of the U-2. In

the cockpit, Powers was shielded from their forward path by the engine and

wings. Maybe the left turn which he had just made, also helped the pilot escape

the full force of the blast. Powers instinctively grasped the throttle with his

left hand, and keeping his right hand on the big control yoke, corrected a

slight drop in the right wing. But then the nose dropped, and no amount of

pulling back on the yoke could bring it back up. Then a violent shaking

erupted, flinging the pilot all over the cockpit. He later reckoned the wings

had come off. "What was left of the plane started spinning, only upside down,”

Powers recalled. Experiencing up to 4g and with his pressure suit now inflated,

the pilot had extreme difficulty trying to make his escape. He was being forced

forward and up, and could not activate the ejection system for fear that his

legs would be chopped off by the canopy rail when the rocket fired and the seat

rose up its track.

The pellets hit the tail and rear fuselage of the U-2. In

the cockpit, Powers was shielded from their forward path by the engine and

wings. Maybe the left turn which he had just made, also helped the pilot escape

the full force of the blast. Powers instinctively grasped the throttle with his

left hand, and keeping his right hand on the big control yoke, corrected a

slight drop in the right wing. But then the nose dropped, and no amount of

pulling back on the yoke could bring it back up. Then a violent shaking

erupted, flinging the pilot all over the cockpit. He later reckoned the wings

had come off. "What was left of the plane started spinning, only upside down,”

Powers recalled. Experiencing up to 4g and with his pressure suit now inflated,

the pilot had extreme difficulty trying to make his escape. He was being forced

forward and up, and could not activate the ejection system for fear that his

legs would be chopped off by the canopy rail when the rocket fired and the seat

rose up its track.

As the spinning fuselage descended through 34,000 feet, Powers realized that he had an alternative means of escape - to bail out. He pulled the canopy release handle, and the canopy sailed away. He tried to reach the destruct switches on the right canopy rail, then changed his mind, thinking that he ought to ensure that he could escape before he operated them. So he pulled the ‘green apple’ handle which activated his emergency oxygen supply, and released his seat belt. Immediately, the centrifugal force threw him halfway out of the aircraft, but he was restrained by the oxygen hoses, which he had forgotten to disconnect. His faceplate had now frozen over. He kicked and squirmed blindly, and suddenly he was free.[13]

On the ground, Major Voronov’s crew saw the target dissolve into interference on their radar screens. They weren’t sure whether this represented a successful kill, or whether the intruder had deployed electronic countermeasures against their radar, such as chaff. Voronov reported his uncertainty up the chain of command. The regiment commander Colonel Pevnyi ordered the adjacent S-75 battery at Beryozovsk, into whose zone of engagement Powers had now flown, to fire at the target. At this battery, Major Nikolai Sheludko and his crew successfully salvo-fired three missiles. They climbed towards what was now a descending mass of debris, comprising the U-2 fuselage, wings and tail (all now separated) and the fragments of the single missile from Voronov’s battery. Two of Sheludko’s missiles either detonated close to the debris, or flew through it and detonated some way further on, as they were automatically programmed to do when no target had been intercepted. (the third had flown off in completely the wrong direction).[14]

By now, Powers had made his escape from the spinning, falling cockpit of the U-2. Once again, he was incredibly lucky. Somehow, he was not hit by the two newly-fired missiles which headed his way, or by the many pieces of aircraft and missile debris which were now falling from the sky.

PVO Confusion

That debris was now creating an even bigger bloom on the radar screens of the PVO’s batteries and command post below. From a third S-75 battery to the north of the city, Major A. Shugayev reported that his crew was tracking targets which appeared to include the enemy aircraft, now descended to 36,000 feet. It was not responding to their IFF (‘identification friend or foe’) interrogation. There was still no outcome reported from Voronov’s battery, or from Sheludko’s. Pevnyi, the commander of the missile regiment, suspected that the targets which Shugayev had identified were the PVO’s own interceptor fighters.

But the district command in Sverdlovsk didn’t even realize that the fighter command post in the same building had some MiGs airborne. Some minutes passed, and still the target was being tracked at 36,000 feet. Pevnyi was ordered to engage the newly-reported target by the most senior PVO man present, deputy district commander Major General Solodovnikov. So Shugayev was cleared to fire, and another three missiles streaked skywards. A short time later, back at the first battery, Voronov finally realized that he had destroyed the intruder with the very first missile. He belatedly reported a confirmed kill.[15]

So what target had Shugayev’s battery just fired at? Captain Boris Ayvazyan was leading the flight of two MiG-19s which had been scrambled from Koltsovo ten minutes before Powers was shot down. They were directed to fly to the north of the original missile engagement zone, towards Perm. The ground controller told Ayvazyan that the target was ahead of him by 10 kilometers, then only five. The pilot looked around for his wingman and found him some way behind, struggling to keep up. At the same moment, Ayvazyan saw an explosion above and to his right, and turned towards it. Was this his target? The flight leader wasn’t sure (in fact, it was probably the first missile from Voronov’s battery exploding and downing the U-2). Shortly after, Ayvazyan saw another explosion off to his right (probably one of Sheludko’s missiles).

A third MiG-19 joined the pair. It was flown by the 356th Regiment commander Gennady Gustov, who had scrambled from their home base at Perm. He was having difficulty communicating with the ground controller, so Ayvazyan relayed his request for instructions. The answer came back: Gustov to return to Perm, Ayvazyan’s pair to land back at Koltsovo and refuel.

Ayvazyan set course for the airfield and decided on a straight-in approach. His wingman was still some distance behind. Ayvazyan saw the runway ahead as he began to descend from 10 kilometers (33,000 feet). Suddenly there was an urgent warning from the controller: "Lose height quickly!” Someone on the ground had realized that fighters and SAMs were now in the same firing zone, although they didn’t explicitly warn Ayvazyan to this effect. Nevertheless, the flight leader reacted intuitively by putting his aircraft into a vertical dive, pulling out only 300 meters (1,000 feet) from the ground. His wingman Safronov was instructed to do the same thing, but no more was heard from him.

Ayvazyan did a circuit of the airfield, hoping that his wingman would rejoin. But Senior Lt Sergei Safronov had been hit by one of the missiles fired from Sheludko’s battery. He ejected from his stricken aircraft, and the parachute deployed, but the unfortunate pilot was found dead on the ground. The wreckage of the MiG fell into a public park near a village to the west of Sverdlovsk.[16]

According to the most detailed published account of the shootdown, least one more missile was fired, from a fourth battery. This one was successfully evaded by Igor Mentyukov, the Su-9 pilot who had been ordered to ram Powers’ plane, as he descended to land at Koltsovo[17] It was nearly 40 minutes after the shootdown before the PVO’s Sverdlovsk command post finally realized that it had shot down the intruder, and stopped trying to track it! [18]

Powers Captured

Powers saw nothing of this. Almost immediately after escaping from the aircraft, his parachute opened automatically. The American realized that therefore he was already below 15,000 feet, where the barostat operated. He couldn’t tell for sure, though, since his faceplate was still frosted over. He undid the clasp and removed it. He floated slowly down, just missed some power lines, and landed in a ploughed field near a village. Two farm workers helped him to his feet and removed the parachute. More people arrived. There was no chance of escape.

NOTE FROM CHRIS POCOCK: I wrote this account of the shootdown in 2005. Since then, new Russian accounts and sources have been published. They suggest that the first SA-2 missile to be fired - and therefore the one that shot down the U-2 - was fired from a different battery to the one that was previously credited. I discuss this new evidence on my website here: https://dragonladyhistory.com/2020/05/01/u-2-mayday-shootdown-gary-powers/

For more from Chris Pocock, sign up for the Cold War Museum Presentation featuring Chris on June 6, 2021, here: Chris Pocock: "The Enduring U-2 Dragon Lady"

Plus: For autographed copies of Spy Pilot: Francis Gary Powers, the U-2 Incident, and a Controversial Cold War Legacy” by Francis Gary Powers, Jr, visit www.spypilotbook.com.

AND

You

can act now to help us preserve Cold War History by making a donation to The

Cold War Museum® at this link: DONATE TO PRESERVE COLD WAR HISTORY

You

can act now to help us preserve Cold War History by making a donation to The

Cold War Museum® at this link: DONATE TO PRESERVE COLD WAR HISTORY

[1] Mikhailov and Orlov article

[2] Mikhailov and Orlov article

[3] Mironov article, p6-7

[4] Lockheed Report SP-179, p188

[5] Powers book, p81

[6] Lt Col V. Samsonov, "Eight Missiles for Powers”, Motherland (the magazine of the PVO Moscow Air Defence District) 30 August 1992; Col Mikhail Voronov, "The Shooting Down of Powers”, abridged from Komsomolets Kubani newspaper in Sputnik: Digest of the Soviet Press, April 1991. Samsonov was in the district command post on 1 May, and Voronov in the first missile battery to engage the U-2. In another article ("U-2: How It Was”, HBO - Independent Military Review, No 28, 1998), Igor Tsisar (who was an officer in Voronev’s battery at Sverdlovsk) alleges that the radar officer at the Chelyabinsk battery was drunk, and the soldier who was supposed to check the fuses was incompetent.

[7] from an article in Popular Science, August 1994, p58

[8] Mentyukov later speculated that his radar screen had been affected by interference from his own, tail-mounted ECM (electronic countermeasures) system. However, it is possible that the small ‘Granger’ ECM box on Powers’ U-2 really did work as hoped against airborne intercept radar! (In Rich and Janos, p162, Rich notes that Kelly Johnson suspected after the shootdown, that the Granger may have acted in the opposite manner to that intended eg as a homing device for the SAMs that were subsequently fired at Powers. There is no evidence to support this speculation and (sadly) much of the rest of the U-2 story as related by Rich and Janos is inaccurate)

[9] Lt Col Anatoly Dokuchaev, "Duel in the Stratosphere - How the Spy Flight of Francis Powers was stopped,” Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) 29 April 1990; Dokuchaev, "Flap of the Overflight Mission”, Air Fleet Herald, Moscow, November-December 1998. In an interview with Trud newspaper in October 1996, Mentyukov claimed that he managed to reach the U-2’s altitude, and as he overtook it, the U-2 was upset by wake turbulence from the interceptor. This led to the spyplane’s break-up and descent. This claim is highly suspect, and Mentyukov did not repeat it when interviewed again for the Air Fleet Herald article. The author prefers the more convincing evidence offered by the ‘official’ Red Star version cited in this footnote, Powers’ own account, and other non-official Russian accounts which are cited here.

[10] Voronov and Tsisar articles, and Penkovsky debrief, as above, where the spy notes that "Powers would have escaped if he had flown 1 or 1.5 kilometers to the right of his flight(path).” Tsisar says that he fabricated his official report, as to why two of the battery’s three missiles didn’t fire. The story that they were prevented from firing because the antenna on the battery’s radar cabin obstructed their line of fire, is not correct, he says. By reporting this as fact, he presumably hoped to draw attention away from the battery’s slow reaction to the target, which caused the U-2 to be out-of-range by the time that the second and third missiles were ready to launch

[11] Powers book

[12] Zaloga book; Penkovsky debrief, NSA 315, p10; Mikhailov, interviewed by Indigo Films for The History Channel, 1999. Mikhailov estimated that the warhead exploded 20 meters behind the U-2

[13] Powers book

[14] Tsisar article

[15] Samsonov and Tsisar articles

[16] Boris Ayvazyan, interviewed by Indigo Films for "Mystery of the U-2”, a film documentary for The History Channel, 1999. In this detailed account, Ayvazyan contradicts earlier-published accounts (Dokuchaev, Samsonov articles), that he saw Shugayev’s missile(s) coming, and instigated his dive without instruction from the ground controllers.

[17] Samsonov article

[18] Pedlow/Welzenbach, p178